What Every AI Image is Missing

AI + Roland Barthes

In his 1980 book “Camera Lucida,” Roland Barthes names the reason some images make us feel something, while others don’t affect us at all. He narrates his experience of looking at photographs of war and starvation and notices that he’s experiencing a detached, low level of interest. The images, despite their shocking subject matter, are banal to him.

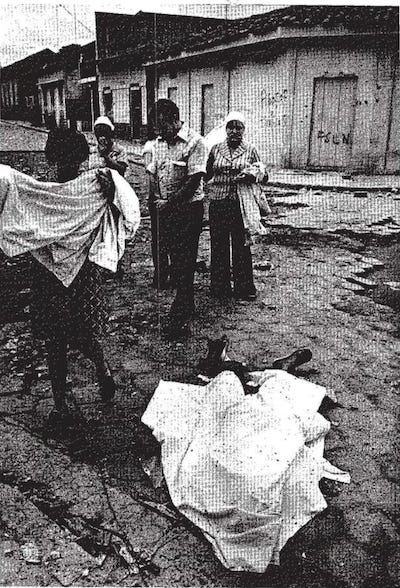

But one image stops him. There is a photograph of a child’s corpse covered by a sheet in a street — a scene from the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1978 by photojournalist Koen Wessig. He notices the child’s weeping mother is carrying another white sheet. “Why this sheet?” Barthes asks himself and suddenly he is thinking about this child’s mother and then his own late mother, for whom “Camera Lucida” is an elegy. He writes that he is feeling disturbed, wounded, even bruised by this image.

Can AI Images Achieve Poignancy?

The “punctum” is the Latin word Barthes finds to describe that surprising and poignant detail in an image that yanks a viewer out of their normal state of viewing and makes them feel something. It can be present in any type of image or work of art, on any topic. But a punctum is always an accidental detail — one that the maker usually isn’t aware of when they make the work.

The punctum shoots out from the image “like an arrow” and pierces the viewer. Some examples he gives of the punctum include:

The dirty fingernails of poet Tristan Tzara in an otherwise formal photograph from 1927.

The beautiful, crumbling Arabic decoration on a wall of a photo taken in Granada in 1857.

The texture of underwear in one of Robert Maplethorpe’s close-ups of genitalia.

My questions are: Can AI produce an image with a punctum? Or is this something that only a human creator can produce? In other words: Can an AI image be poignant?

What Barthes Would Say

Barthes says the punctum “is offered by chance … the scene is in no way ‘composed’ according to a creative logic.” And the term “creative logic” is a perfect, exact synonym of “generative AI.”

Of those thousands of images that don’t move him (which he dubbed as “studium”) he says: “What I feel about these photographs derives from an average affect, almost from a certain training.”

An AI-generated image is trained to be an average of millions of other images. So no, according to Barthes, AI could not produce a punctum.

The Messiness We Will Miss

To me, it is not so clear-cut. But a punctum is a record of the messy, eclectic reality we inhabit — the one that I love and worry about losing in the age of AI.

The small, strange detail that becomes a punctum for us is a product of the real world, the physical world we live in. It is an anomaly or off-kilter ingredient that was not edited out or smoothed out or filtered out. It is inimitable and unintentional and disruptive. Ironically, the detail that doesn’t belong makes the image “real” for us.

A punctum subverts our expectations, whereas AI images yearn to fulfill our expectations. They depend on quick apprehension and tropes (which is why inherent bias is a danger to us). AI images feed off of heterogeneity, generalization, and commercialism.

I’m interested in injecting more authenticity into content, not stripping it out.

A note for marketers:

For the same reason we favor original photography over stock photography in marketing, I urge my clients to keep filler words in (“um,” “like,” “you know,” etc.) when they quote faculty and students. From a branding point-of-view, these irregularities increase conspicuity and memorability — two effective ingredients in brand impressions. Filler words are the human-ness of someone’s voice in real time; the result of the beautiful, glucose-hungry brain running slowly to express ideas, with all of the cognitive errors and quirks that attend it.

Ultimately, a punctum is defined only by the human agent perceiving it. That is because a punctum effects a biological reaction in the viewer. “I recognize, with my whole body, the straggling villages I passed through on my long-ago travels in Hungary and Romania,” Barthes says, describing his reaction to a dirt road in a photograph of Central Europe.

What About Video & Deepfakes?

This discussion can’t really pertain to video — only to still images (and only to photographic-like images vs. painterly images if we are in conversation with Barthes). Because yes, deepfakes and AI-generated video can absolutely affect us emotionally, reach us, compel us. This is what makes the implications of that technology so terrifying.

After all, haven’t we been responding emotionally to computer-generated images (CGI) for decades now? Women (self included) wept while watching Wonder Woman at the poignancy of Amazonians on the battlefield. Pixar movies, especially “Up,” “Inside Out,” “Toy Story,” “Finding Nemo,” are very good at making us cry.

What About AI Hallucinations?

An AI “hallucination” is an error within an AI response. I asked Hugging Face to generate an image of the late Dame Maggie Smith with its free Stable Diffusion demo. The image is below. Her double earring is a hallucination and the wonky tailoring on her lapel is another.

Like a punctum, hallucinations are small, strange details that are accidental and also disruptive. But the punctum is evidence of the physical world; the hallucination is evidence of a synthetic one. Thus far, our brains don’t (at least, mine doesn’t) respond to these kinds of details with the recognition, memory, and longing that poignancy requires.

However, maybe a hallucination can be an anti-punctum. The hallucinations and the other errors in this photo make me appreciate things that are true and real about Maggie Smith that I never noticed before:

She was immaculate about her tailoring.

She did not wear large pearl earrings and usually chose no earrings at all.

Her eyes never bulged that much, but occasionally slightly, like my grandmother's, who also had Graves' disease.

Her cheeks were fuller, which made her look high-born and down-to-earth at the same time.

Her hair was less brown mouse and more silver fox.

To identify what AI got wrong, I am compelled to search for real photographs of Maggie Smith. I’m noticing the small details about her. I’m wondering if her children remember those things about her. I’m thinking about things I must try to remember about my mother before she is gone. I’m thinking of all the small, strange details that make up the fullness of her and can never be replicated; the small, strange details that I will always recognize, with my whole body.

The full text of Camera Lucida is available on the Internet Archive.